Introduction to GRE

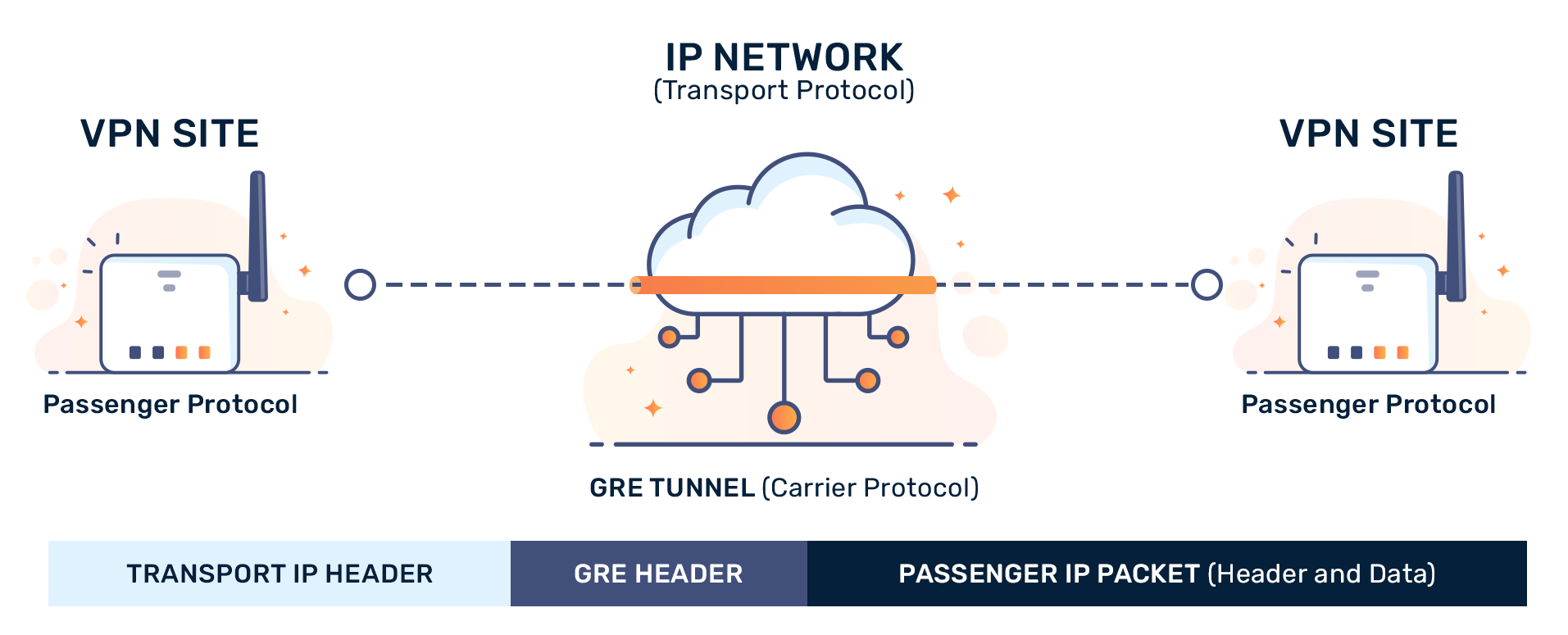

GRE stands for Generic Routing Encapsulation. It's a protocol that connects two servers, or sites, together. GRE tunnels often transport multiple layers of data and are multicast. This means that tunnels can encapsulate virtually any traffic across two points and are fairly easy to configure.

One more thing to note is that there are other forms of site-to-site tunnels. Some examples include IPIP tunnels, and GRETAP tunnels.

Uses for GRE

While GRE tunnels can be used to transport video, website traffic, and basically anything, they're notably used in the following ways:

- Allowing unsupported protocols to be transported across a network. For example, allowing IPv6 communication over a network that is otherwise IPv4-only.

- DDoS protection. Traffic is routed to and from a tunnel endpoint from a provider that can remove dirty traffic.

- Creating a virtual link between two networks for routing. A router can be connected to a virtual network that enables BGP communication among multiple networks without requiring a physical connection like those used in conventional IXPs.

How does GRE work

As mentioned previously, GRE tunnels encapsulate traffic. This means tunnels do not care about the traffic you send over them. So long as the tunnels are appropriately configured, traffic traverses across the open internet in plain text. Tunnels do not encrypt traffic on their own. You can use encrypted tunneling through VPN software.

Also, GRE tunnels are stateless. When you first configure a tunnel, it is analogous to using unregistered airmail. You load your packages on board (i.e., your packets/data) and send them off to your destination server. Unfortunately, the destination is never made aware of this flight and will only know about the incoming data once it arrives at a given destination.

However, you may ask: “How does the destination server know where to send a response?” All packets encapsulated through GRE include both the destination and source, allowing both points to know where to send data.

The stateless nature of GRE further raises issues. If you, for example, set your MTU (Maximum Transmission Unit) too high, and the destination is configured not to accept packets that large, you will receive no reply or response. The only way to know whether one point’s packets are reaching a destination is through reviewing the traffic on the receiving server. This reduces overhead on transmissions, but increases the difficulty of debugging the specific issue being caused by the “cargo” on the “plane.”

With that said, GRE tunneling is supported on many platforms. You will often find them built-in to enterprise routers, but they are available on virtually all Linux platforms with the ip_gre module (in software). The previously-mentioned routers tend to have hardware acceleration to reduce load. Keep this in mind when setting up tunnels, as you may encounter problems with the overhead added by encapsulating data (there are an additional 24 bytes per GR-encapsulated packet).