You can spend a lot of time squeezing milliseconds out of your frontend, APIs, and caching layers. But if your database sits far away from your users, every request still pays the cost of a long round trip.

When that happens, devs usually reach for workarounds: more caching, denormalized reads, background sync jobs, or other techniques to hide the latency. These approaches work, but they add complexity quickly.

The underlying issue is simpler. For most applications, database reads are still centralized in a single region, and distance is unavoidable. This isn’t really a caching problem — it’s a data locality problem.

So the obvious question is: how bad does it actually get as users move farther away from the database?

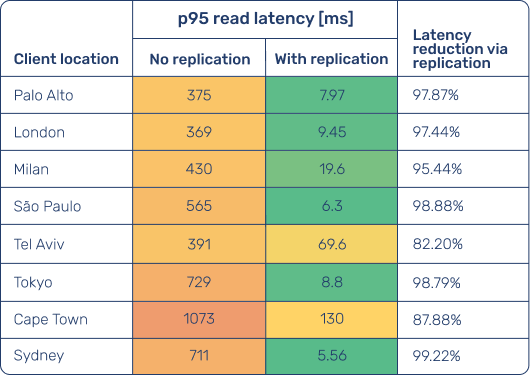

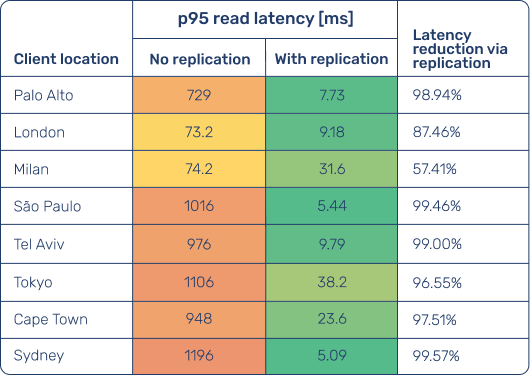

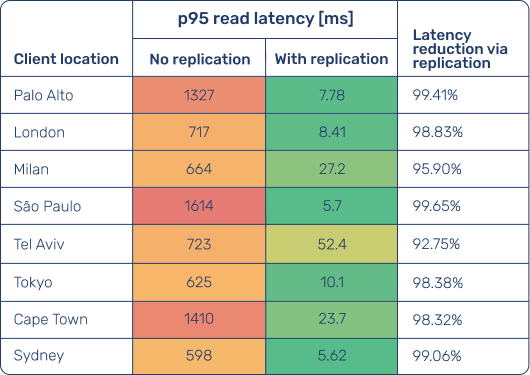

To find out, we measured p95 latency in Bunny Database across increasing distances between the database and client locations. We then measured p95 latency for the same set of locations with read replication enabled, allowing reads to be served from regions local to the user, and compared the results.

Benchmark setup

Since Bunny Database is based on SQLite, we chose the Chinook dataset, a commonly used sample SQLite database with a realistic transactional schema.

While the database engine itself is very fast, making query execution time negligible compared to network latency, we still opted for a realistic read query rather than a trivial SELECT 1, to better reflect how applications actually access data:

WITH recent_invoices AS (

SELECT

InvoiceId,

InvoiceDate,

Total

FROM invoices

WHERE CustomerId = ?

ORDER BY InvoiceDate DESC

LIMIT ?

)

SELECT

ri.InvoiceId,

ri.InvoiceDate,

ri.Total,

ii.InvoiceLineId,

ii.Quantity,

ii.UnitPrice,

t.TrackId,

t.Name AS TrackName,

a.Title AS AlbumTitle,

ar.Name AS ArtistName,

g.Name AS GenreName

FROM recent_invoices ri

JOIN invoice_items ii ON ii.InvoiceId = ri.InvoiceId

JOIN tracks t ON t.TrackId = ii.TrackId

JOIN albums a ON a.AlbumId = t.AlbumId

JOIN artists ar ON ar.ArtistId = a.ArtistId

LEFT JOIN genres g ON g.GenreId = t.GenreId

ORDER BY

ri.InvoiceDate DESC,

ii.InvoiceLineId ASC;

Bunny Database is available in 41 regions worldwide, but to keep the benchmark focused, we limited the experiment to a smaller, representative set of locations:

- Ashburn, Frankfurt, and Singapore as primary regions: these are commonly offered anchor regions across database providers and serve as practical reference points for North America, Europe, and Asia-Pacific.

- Palo Alto, London, Milan, São Paulo, Tel Aviv, Tokyo, Cape Town, and Sydney as client locations and read replica regions: this set spans the globe and represents increasing geographic distance from Ashburn.

As for technical implementation, we used Grafana k6 to conduct p95 latency measurements. Since the benchmark needed to run from the selected client locations, we ran k6 on Magic Containers, the bunny.net managed container service that shares the same regions with Bunny Database.

This setup allowed us to simulate the round-trip latency experienced by users in different parts of the world when accessing a centralized database.

Benchmark results

The tables below show p95 read latency measured from each client location, first with a single-region database setup and then with read replication enabled, where queries are served from replicas deployed in the same regions as the clients, rather than always being routed to the primary region.

Client locations are ordered by increasing distance from Ashburn, and the same ordering is reused for Frankfurt and Singapore for consistency.

Read latency by client location

Primary region: Ashburn

Primary region: Frankfurt

Primary region: Singapore

Notes on methodology

Each data point represents the p95 latency observed within a single benchmark run consisting of hundreds of requests from a given client location. We didn’t average results across multiple runs, which means transient network effects are preserved rather than smoothed out.

This reflects real-world conditions, where user requests experience the network as it is, not as an average.

Read replicas were deployed in the same regions as the client workloads, making this a best-case scenario for read locality. As a result, the “with replication” measurements represent the upper bound of what can be achieved when reads are served locally.

In practice, results will vary depending on region coverage, routing, and workload patterns — but the underlying trend remains the same.

What these results mean in practice

- Distance dominates latency in single-region setups: without replication, read latency increases sharply as client locations move farther away from the primary region, often reaching hundreds of milliseconds for intercontinental access.

- Read replication consistently collapses read latency across regions: with replication enabled, p95 read latency drops to single- or low double-digit milliseconds in nearly all locations, regardless of distance from the primary region.

- The biggest gains appear for far-away users: intercontinental client locations see latency reductions of up to 99%, turning multi-hundred-millisecond round trips into near-local reads.

- Replication doesn’t eliminate all variability: some locations still show higher p95s than others, reflecting real-world network conditions and routing differences rather than database performance.

- The pattern holds across all primary regions tested: whether the primary region is Ashburn, Frankfurt, or Singapore, the overall trend remains the same: distance hurts without replication, and replication largely neutralizes it.

The takeaway

Our benchmark shows that database placement has a first-order impact on user experience for global applications. A single-region database may perform well for nearby users, but quickly becomes a bottleneck as traffic spreads geographically.

By serving reads from regions close to users, read replication shifts latency from being distance-bound to being dominated by local network conditions without requiring application-level caching or architectural workarounds.